You will never become saint unless you want to be a saint. It is indispensable to say to oneself frequently, “I want to be a saint.” That is, after all, what God wants for each of us. One who says, “I want to be a saint” is simply aligning his own will with the glorious will of God. “For this is the will of God, your sanctification” (1 Th 4:3).

If, at least once a day, you say to yourself, “I want to be saint,” a number of things will happen. You will begin to adjust your perspective on life. You will set your priorities in order. Things that you judged important will become unimportant, and things that you judged unimportant will become important.

Tuesday, October 31, 2006

Saints and Sinners

The Cistercian monk, Don Marco (Fr. Mark Daniel Kirby, O.Cist.) is a light in the monastic window for those of us who are trying to make our way in a noisy and confused world. "There is no such thing as a happy sinner," Dom Marco wrote in a recent post on his Vultus Christi, "and there is no such thing as a miserable saint."

Monday, October 30, 2006

Miserere Nobis ...

In a society where the highest moral principle is the refusal to make moral judgments and where the quintessential moral gesture is not pharisaical righteousness but rather an indifferent shrug: a frightened young woman lets a Planned Parenthood worker talk her into an abortion; the man who got her pregnant loses interest and disappears; a young African, adopting the moral nihilism of the condom distribution program that has compounded his despair and self-loathing, knowingly exposes his sexual partner to Hepatitis C; a corporate executive takes a short-cut, exposing thousands of investors to economic ruin.

Meanwhile, those who by the sheer grace of God have avoided these things take far more credit for their rectitude than is justifiable, it having been due largely to the accidents of upbringing and opportunity. The conservative among them insist on the immorality of those who do such things; the liberals (except in the case of the corporate executive) blame the “society.”

But Raymund Schwager saw the larger moral picture:

Meanwhile, those who by the sheer grace of God have avoided these things take far more credit for their rectitude than is justifiable, it having been due largely to the accidents of upbringing and opportunity. The conservative among them insist on the immorality of those who do such things; the liberals (except in the case of the corporate executive) blame the “society.”

But Raymund Schwager saw the larger moral picture:

Sins, especially serious and conscious ones, begin in the depths of the heart and they often have a long prehistory, in which many people bear different amounts of responsibility and in which it often depends on accidental circumstances as to whether things get as far as an outward, punishable deed and who commits it.The indifferent shrug is fostered by Christian sentimentalists who, with the best of motives, perpetuate the idea that God’s mercy completely supersedes God’s justice. Here’s what the Polish-American poet Czeslaw Milosz had to say about that:

Religion, opium for the people. … A true opium for the people is a belief in nothingness after death – the huge solace of thinking that for our betrayals, greed, cowardice, murder we are not going to be judged.A Christian will recognize his own subtle contributory complicity without exonerating the individual who commits the moral offense, for to do that would be to discourage him from taking moral responsibility for his acts, and thereby to deprive him of perhaps the last shred of his moral dignity. Here’s how Max Scheler puts it:

... it is very superficial to say that one should rest content with “not judging” the guilt of others but rather be mindful of one’s own individual guilt. ... one should not only be mindful of one’s own guilt but feel oneself genuinely implicated in the guilt of others and in the collective guilt of one’s age; one should therefore regard such guilt as one’s “own,” and share in the repenting of it. That is the true sense of the mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa.

Friday, October 27, 2006

Suffering in the Meantime ...

Speaking of Jesus at the Last Supper, Hans Urs von Balthasar writes:

He does not act in the Cenacle as a soloist before an auditorium that listens to him, as an actor on stage before onlookers in theater seats. He always acts in such a way that he draws those who belong to him into his act.My wife’s continued ill-health and her patience in dealing with the many difficulties involved brings to mind one of von Balthasar’s reflections in the final volume of his Theo-Drama series. The genuine disciple of Christ, von Balthasar writes, “is promised chiefly pain and difficulty; he is urged to show courage, trust and confidence in divine help.”

For the Old Testament believer, temptation and even misfortune was primarily a sign that he had become guilty before God; in extreme instances (Job), it represented a baffling evil. For the Christian it is rather a confirmation of his discipleship of the Lord. ... Recognizing his suffering as Christ’s, and as a grace, he can enjoy the Christian hope that – in however hidden a manner – this suffering, in union with Christ’s, will promote the salvation of the world.The suffering that is meaningless to worldly eyes is experienced by a Christian as a participation in Christ’s Passion – “making up for what is lacking in the suffering of Christ.” It contributes in real but inscrutable ways to both the sanctification of the sufferer and the redemption of the world. The meaning a Christian experiences in the midst of seemingly meaningless suffering, however, encompasses the meaninglessness rather than eliminating it. One thinks of that stunning line from a Robert Frost poem in which Job interrogates God, complaining about the senseless suffering he had to endure. God replies: "It had to seem unmeaning to have meaning."

The Present Time

In the Gospel reading at Mass today, Jesus says to the crowds:

Today there is “a cloud rising in the west.” Indeed, there are two of them as far as I can see. In these blog posts, I have often expressed concern over two rapidly developing trends: on one hand, the cultural and moral disorientation of Western societies, a conspicuous feature of which is the West’s semi-official repudiation of the Judeo-Christian soil out of which it grew and by which its best moral and social impulses were long nourished, and, on the other hand, the growing world-wide threat posed by a very intricate network of technologically sophisticated and religiously benighted Islamic jihadists.

It’s clear to me and to many that the liberal-libertine-Left has lost its moral compass and become intellectually bankrupt, running on the fumes of its contempt for the current president and reiterating incessantly mantras that have long since ceased to have any relationship to reality. The conservatives have their own special problems, I grant. I think what Peggy Noonan wrote today in the Online (WSJ) OpinionJournal about Republican conservatives (which, by the way, was critical of George Bush; my liberal friends will love that) is true of those of us cultural conservatives who are not Republicans. She said conservatives “endure the disadvantages of being conservative because they actually believe in ideas, in philosophy, in an understanding of the relation of man and the state.”

I am a social conservative because I am in principle a traditional Christian. My conservatism is religious, moral, and cultural; it is political only coincidentally. That being the case, and this being the age that it is, I don’t expect everyone to agree with me. But I do feel strongly that the direction in which our culture is headed is disastrous, and, along with my colleagues at the Cornerstone Forum, I would like to be a small part of the conversation about how that direction might be altered.

To my friends dismayed by my conservative tendencies of late, I can at least say this: For all my many faults, I have either an impressive or a sorry (depending on where you stand) record of course-reversals dictated by the recognition of the errors of my earlier ways. On several notable occasions over the years I have publicly repudiated points of view which I had previously held and ardently espoused, and I have a list of former friends to prove it. Mercifully, however, many of the friends who complained of these moral and political course-corrections remained friends. After all, there’s more to life than politics and the culture wars.

In light of this history, those exasperated by my more traditional view of things have one reassurance: If I am wrong, and if I can be made to see the error of my ways, I will disavow my position with the same alacrity and remorse with which on several occasions I have declared myself in error in the past. Many of those dismayed by my conservativism/traditionalism, on the other hand, have felt no need to change their basic point of view for the last 40 years. There must be a moral equanimity that accompanies such consistency, and it must have its own special reward, but it doesn’t seem to me to be worth the price. There have been many extremely problematic changes in these last few decades. Fidelity to principle is a virtue, but not when, over time, the moral consequences of the principle to which one remains wedded have reversed.

I am supremely untroubled by the possibility that my assessment of things might be incompatible with, say, whatever the Republican or Democratic party may be espousing, but I would be troubled indeed to find myself at odds with long-standing moral, theological, or social teachings of the Christian tradition generally and the Catholic Church specifically. If anyone really wants to change my mind about anything (and it’s here to be changed), show me where I have departed from the Christian tradition as it has been preserved and developed by the Church’s magisterium, and I will be penitential putty in your hands.

Thanks for stopping by what passes for the Cornerstone Forum’s virtual front porch. Don’t let me do all the talking. Post a comment if you feel moved to do so, and invite your friends over. We’ll continue this conversation with as much candor and charity as we can muster.

When you see a cloud rising in the west you say immediately that it is going to rain–and so it does; and when you notice that the wind is blowing from the south you say that it is going to be hot–and so it is. You hypocrites! You know how to interpret the appearance of the earth and the sky; why do you not know how to interpret the present time?The power of the spirit of the age (against which St. Paul warned us) is such that it is often maddeningly difficult to interpret “the present time.” Depending on whatever preconceptions, weltanschauung, or ideological cast of mind observers may harbor, they can interpret in radically different ways the meaning and likely consequences of the same event. The assessments will not, however, be equally valid. However strongly one might feel about one’s own assessment, a recognition that one might be in error is healthy, though it need not and should not cause one to be timid about expressing convictions about which one is truly convinced.

Today there is “a cloud rising in the west.” Indeed, there are two of them as far as I can see. In these blog posts, I have often expressed concern over two rapidly developing trends: on one hand, the cultural and moral disorientation of Western societies, a conspicuous feature of which is the West’s semi-official repudiation of the Judeo-Christian soil out of which it grew and by which its best moral and social impulses were long nourished, and, on the other hand, the growing world-wide threat posed by a very intricate network of technologically sophisticated and religiously benighted Islamic jihadists.

It’s clear to me and to many that the liberal-libertine-Left has lost its moral compass and become intellectually bankrupt, running on the fumes of its contempt for the current president and reiterating incessantly mantras that have long since ceased to have any relationship to reality. The conservatives have their own special problems, I grant. I think what Peggy Noonan wrote today in the Online (WSJ) OpinionJournal about Republican conservatives (which, by the way, was critical of George Bush; my liberal friends will love that) is true of those of us cultural conservatives who are not Republicans. She said conservatives “endure the disadvantages of being conservative because they actually believe in ideas, in philosophy, in an understanding of the relation of man and the state.”

I am a social conservative because I am in principle a traditional Christian. My conservatism is religious, moral, and cultural; it is political only coincidentally. That being the case, and this being the age that it is, I don’t expect everyone to agree with me. But I do feel strongly that the direction in which our culture is headed is disastrous, and, along with my colleagues at the Cornerstone Forum, I would like to be a small part of the conversation about how that direction might be altered.

To my friends dismayed by my conservative tendencies of late, I can at least say this: For all my many faults, I have either an impressive or a sorry (depending on where you stand) record of course-reversals dictated by the recognition of the errors of my earlier ways. On several notable occasions over the years I have publicly repudiated points of view which I had previously held and ardently espoused, and I have a list of former friends to prove it. Mercifully, however, many of the friends who complained of these moral and political course-corrections remained friends. After all, there’s more to life than politics and the culture wars.

In light of this history, those exasperated by my more traditional view of things have one reassurance: If I am wrong, and if I can be made to see the error of my ways, I will disavow my position with the same alacrity and remorse with which on several occasions I have declared myself in error in the past. Many of those dismayed by my conservativism/traditionalism, on the other hand, have felt no need to change their basic point of view for the last 40 years. There must be a moral equanimity that accompanies such consistency, and it must have its own special reward, but it doesn’t seem to me to be worth the price. There have been many extremely problematic changes in these last few decades. Fidelity to principle is a virtue, but not when, over time, the moral consequences of the principle to which one remains wedded have reversed.

I am supremely untroubled by the possibility that my assessment of things might be incompatible with, say, whatever the Republican or Democratic party may be espousing, but I would be troubled indeed to find myself at odds with long-standing moral, theological, or social teachings of the Christian tradition generally and the Catholic Church specifically. If anyone really wants to change my mind about anything (and it’s here to be changed), show me where I have departed from the Christian tradition as it has been preserved and developed by the Church’s magisterium, and I will be penitential putty in your hands.

Thanks for stopping by what passes for the Cornerstone Forum’s virtual front porch. Don’t let me do all the talking. Post a comment if you feel moved to do so, and invite your friends over. We’ll continue this conversation with as much candor and charity as we can muster.

The Reckless Experiment Continues

Ryan Anderson’s piece on the First Things weblog On the Square is well worth reading. He writes of the October 25th decision of the New Jersey Supreme Court erasing the distinction between marriage as understood for millennia and the sundry arrangements that, in attempting to approximate it, manage only to mock it. Such fashionable acts of what Anderson aptly calls the new judicial aristocracy are not just morally and rationally dubious; they are anthropologically reckless in the extreme, dismantling culture's central institution and vastly compounding the ticking time-bomb of great numbers of children growing up in the shifting sands of social experiment without a father and a mother.

But Anderson’s most important point has to do with the down-stream ramifications of the New Jersey decision: the suppression of free speech and the curtailment of the free exercise of religion. Once again, those who coo about diversity are putting laws in place that are likely to turn the public expression of a moral and social principle based on nature and on the wisdom of the ages into a hate crime.

But Anderson’s most important point has to do with the down-stream ramifications of the New Jersey decision: the suppression of free speech and the curtailment of the free exercise of religion. Once again, those who coo about diversity are putting laws in place that are likely to turn the public expression of a moral and social principle based on nature and on the wisdom of the ages into a hate crime.

Thursday, October 26, 2006

Peace and Truth

In today’s Gospel reading, Jesus announces that he has come to bring, not peace, but the sword of division. That has often been interpreted at the historical level as a reference to the divisions that were occurring during Jesus’ lifetime and especially in the decades following his death between Jews who became followers of Christ and those who didn’t. As with so many of the New Testament’s historical references, however, there is an even more significant anthropological element: The world’s oldest and most reliable mechanism for creating “peace” – “the peace the world understands” – is the unifying power of a collective animosity focused on a single victim or a small, easily identifiable group of victims. It is the (socially) generative power of this “scapegoating” mechanism that has provided humans with social solidarity on the cheap since the beginning of culture.

By revealing on the Cross the innocence of the victims of our generative animosity, Christ destroys the social unity and the emotional and moral consensus it brings about, without which the division referred to in today’s Gospel reading rise quickly to the surface. Contrary to what we often think, however, the underlying problem is not primarily a moral one; rather it is an anthropological one, namely: how to overcome such division, not on the cheap by joining in a shared animosity, but in truth?

On this I would like to share a few sentences from the posthumously published Banished from Eden, by Raymund Schwager, SJ:

By revealing on the Cross the innocence of the victims of our generative animosity, Christ destroys the social unity and the emotional and moral consensus it brings about, without which the division referred to in today’s Gospel reading rise quickly to the surface. Contrary to what we often think, however, the underlying problem is not primarily a moral one; rather it is an anthropological one, namely: how to overcome such division, not on the cheap by joining in a shared animosity, but in truth?

On this I would like to share a few sentences from the posthumously published Banished from Eden, by Raymund Schwager, SJ:

The challenge is to find new and much more difficult ways to create unity without scapegoating. Modern psychology and sociology have long pointed to the problem of projections, yet they have scarcely changed anything. Criticizing collective projections amounts to little or nothing as long as we are unable to achieve the unity among humans beings necessary for human life by other means. Satan, or the scapegoat mechanism with its projections, is thus the ‘ruler of this world’ because he spontaneously brings about this unity, although in a deceptive fashion and at the expense of others. To gain victory over him means to create unity both by owning up to our failings, especially those of which we are not aware (original sin), and by practicing forgiveness ever anew. [163]Which reminds me of what I think might be the most important passage in René Girard’s Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World:

In reality, no purely intellectual process and no experience of a purely philosophical nature can secure the individual the slightest victory over mimetic desire and its victimage delusions. Intellection can achieve only displacement and substitution, though these may give individuals the sense of having achieved a victory. For there to be even the slightest degree of progress, the victimage delusion must be vanquished on the most intimate level of experience. [399]As I have often said from the podium: we humans have to be in the mood for truth. We are usually in the mood for lies and half-truths. The Church’s liturgy is there to put us in the mood for truth, and the presence of Christ in the Church’s sacramental life is the essential content of the truth for which we long once we have been put in the mood, for He is the Way, the Truth, and the Life.

"Hang in there mate."

A young friend of mine sent me a kind email in response to the last blog post. It epitomizes the spirit I often find among younger people of faith, so I thought I would share the last sentence of the email with you:

... in years to come, as the particular complexities of the baby-boomer generation move from centre-stage in the West, it may well be that "Violence Unveilied" will have more of the impact you initially hoped it would (as it already has in me).I omit his name, but the fact that he signs off with "Hang in there mate..." suggests correctly that he hails from Down Under. I'm grateful to him and to all those faithful members of his generation, on whom so many of our hopes today depend.

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

Apologies

I apologize for the tone of the last blog post, though not for its essential content. I dashed it off in the wee hours of the morning and in the midst of other worries related to my wife's ill-health (though that is no excuse). It gave vent to a long-standing exasperation I have felt with the university administrators and university professorates at many Catholic colleges and universities. I said the Georgetown move was disheartening. Indeed it is; but one can always feel heartened by the many marvelous Jesuits who have kept a light in the window during this long, sad period of Jesuit self-parody. In recent blog posts I have quoted Henri de Lubac, SJ, Raymund Schwager, SJ, Edward Oaks, SJ, and others. May the religious order they loved and served be rekindled by spirits such as theirs.

Moral Muddle at Georgetown

For years I have had the special burden of knowing that I wrote a book on the dust jacket of which there appeared a glowing endorsement by Fr. Robert F. Drinan, SJ. Fr. Drinan has been the New York Times step-and-fetch-it Catholic dissident for decades. He was a Massachusetts congressman for ten long years, until he was ordered to resign by John Paul II. During his time as a congressman and since he has served as an always reliable “Catholic” proponent of abortion and just about every other feature of the libidinous-Left agenda.

Admittedly, at the time I wrote the book I had not entirely cleared my head of the (illiberal) "liberal" pieties which hung like a fog in the air, but even then I found the Drinan kudos embarrassing. Though the endorsement was replaced on the paperback edition by ones from slightly less aggressive dissidents, the fact that Fr. Drinan found the book to his liking (had he read it more carefully, he wouldn’t have) is symptomatic of the sundry reasons I don’t much mention the book in public any more. It was written to argue for the great value of the work of René Girard and, in passing, to persuade secular liberals that their best ethical principles derive from the Gospel and that their worst ethical blunders derive from their refusal to take the Gospel seriously. If the dust-jacket endorsements are any indication, the book failed in this latter effort even if it succeeded in the former one. I’m pained to say that. Why do I bother to say it?

Well, because at a ceremony on October 23rd, Georgetown University Dean T. Alexander Aleinikoff announced the establishment of the Robert F. Drinan, SJ, Chair in Human Rights. Fr. Drinan has argued persistently and forcefully against the banning of partial-birth abortion, and he has taken the most un-Catholic position on the central moral issue of our time. For decades he has fought against the legal recognition of the "human rights" of millions of innocent children who have been killed in the wombs of their mothers. He is the incarnation of the crisis in American Catholicism, an insult to the Church he was ordained to serve and a special scandal to the Jesuit order, which can find no honor too lofty to confer upon him.

Now that the aging figures that have so betrayed the Church and so contributed to the moral confusion of the last two or three generations of Catholics are reaching the age when perfunctory honors are bestowed, we had better prepare ourselves for more of this. But this move by a Jesuit university that was once Catholic in more than name only, is as mind-boggling as it is deeply disheartening.

Admittedly, at the time I wrote the book I had not entirely cleared my head of the (illiberal) "liberal" pieties which hung like a fog in the air, but even then I found the Drinan kudos embarrassing. Though the endorsement was replaced on the paperback edition by ones from slightly less aggressive dissidents, the fact that Fr. Drinan found the book to his liking (had he read it more carefully, he wouldn’t have) is symptomatic of the sundry reasons I don’t much mention the book in public any more. It was written to argue for the great value of the work of René Girard and, in passing, to persuade secular liberals that their best ethical principles derive from the Gospel and that their worst ethical blunders derive from their refusal to take the Gospel seriously. If the dust-jacket endorsements are any indication, the book failed in this latter effort even if it succeeded in the former one. I’m pained to say that. Why do I bother to say it?

Well, because at a ceremony on October 23rd, Georgetown University Dean T. Alexander Aleinikoff announced the establishment of the Robert F. Drinan, SJ, Chair in Human Rights. Fr. Drinan has argued persistently and forcefully against the banning of partial-birth abortion, and he has taken the most un-Catholic position on the central moral issue of our time. For decades he has fought against the legal recognition of the "human rights" of millions of innocent children who have been killed in the wombs of their mothers. He is the incarnation of the crisis in American Catholicism, an insult to the Church he was ordained to serve and a special scandal to the Jesuit order, which can find no honor too lofty to confer upon him.

Now that the aging figures that have so betrayed the Church and so contributed to the moral confusion of the last two or three generations of Catholics are reaching the age when perfunctory honors are bestowed, we had better prepare ourselves for more of this. But this move by a Jesuit university that was once Catholic in more than name only, is as mind-boggling as it is deeply disheartening.

Tuesday, October 24, 2006

Christianity in Decline ...

Tom Bethell has written (here) a sad but I fear accurate assessment of the demise of Christianity in the Middle East, North Africa, and increasingly Europe. In it he says:

The same is true of the Norwegian journalist Fjordman, whose recent article was quoted at length here. In it he writes:

Lebanon is a microcosm, and an object lesson. It is a country where Christianity is on the wane. By one estimate, it was once over 70 percent Christian; today it is less than half that. Shi'ite Muslims alone probably outnumber Lebanese Christians (mostly Maronite). The decline may be greater than that. The Washington Post reported a few years ago that Lebanon has not conducted a census for about 50 years "out of concern that the evidence of Christian decline and Shi'ite Muslim advancement might fuel sectarian tension."“Something similar is happening,” Bethell writes, “although more slowly, in Europe. … Plainly, the rise of Islam in Europe is directly related to the fall of Christianity.”

A similar pattern holds across the Middle East, where the Christian downfall has been dramatic. The Catholic Archbishop of Algeria, interviewed recently by the New York Times, described "the ebbing of Christianity from North Africa's shores as Islam spreads across Europe." In 1958, there were more than 700 churches in the country where St. Augustine was born and died. Now there are about 20, and they are mostly empty. "The rest have been converted into mosques or cultural centers or have been abandoned." The archbishop says Mass for a remnant of 20 people.

"Into the void are coming Islam and Muslims," Daniel Pipes wrote in the New York Sun two years ago. "As Christianity falters, Islam is robust, assertive and ambitious." He foresaw a time when Europe's "grand cathedrals will appear as vestiges of a prior civilization." Until they are transformed into mosques, that is.Bethell sells Pope Benedict a little short in my opinion, but his article performs what may be the premier task of public intellectuals today: it speaks inconvenient truths.

The same is true of the Norwegian journalist Fjordman, whose recent article was quoted at length here. In it he writes:

The anti-Christian element seems to be a trait shared by multiculturalists in all Western countries. … The First Commandment of Multiculturalism is: Thou shalt hate Christianity and Judaism. Multiculturalists also hate nation states, and they even hate the Enlightenment, by insisting that non-Western cultures should be above scrutiny.

"Sin" ...

An article last Friday in the New York Daily News about the New York Supreme Court ruling requiring Catholic institutions to provide female employees with birth control coverage regardless of their religious scruples in the matter, begins this way:

Even if they believe contraception is "sinful," religious social service organizations must provide female employees with birth control coverage in their health insurance, the state's highest court unanimously ruled yesterday.Later in the article the sneer quotes around the word sinful recur. The question is: what is being sneered at? Is it the "sinfulness" of contraception, the very idea of "sin," or the antiquated religion that still insists of using such an outmoded vocabulary?

NARAL Pro Choice New York and Family Planning Advocates of New York State praised the ruling.As long as the separation between Church and State gives way in right direction, those who use it as a slogan of convenience see no problems.

Monday, October 23, 2006

Mission, Meaning, and Posterity

This from John Henry Cardinal Newman:

God has created me to do him some definite service; he has committed some work to me which he has not committed to another. I have my mission – I never may know it in this life, but I shall be told it in the next. Somehow I am necessary for his purposes, as necessary in my place as an Archangel in his – if, indeed, I fail, he can raise another, as he could make the stones children of Abraham. Yet I have a part in this great work; I am a link in a chain, a bond of connection between persons. He has not create me for naught. …A link in a chain, a bond of connection between persons … this, as one grows older, seems to go to the heart of the matter. Scientific facts may exist independently of the acts that communicate them, but, in a world created by a Triune God, the supreme truth exists only where truthful people are willing and able to tell one another the truth. How we do this, and however well or inadequately we do it, the act of witnessing is integral to the mission. As R. R. Reno succinctly put it in the November issue of First Things:

Therefore I shall trust him. Whatever, wherever I am, I can never be thrown away. If I am in sickness, my sickness may serve him; in perplexity, my perplexity may serve him; if I am in sorrow, my sorrow may serve him. My sickness, or perplexity, or sorrow may be necessary causes of some great end, which is quite beyond us. He does nothing in vain; he may prolong my life, he may shorten it; he knows what he is about, he may take away my friends, he may throw me among strangers, he may make me feel desolate, make my spirits sink, hid the future from me – still he knows what he is about. [quoted: Magnificat, Vol. 8, No.8]

None of us can reinvent a Christian literary imagination, political theory, scientific culture, or systematic theology on our own, because a Christian intellectual culture is a collective, multigenerational project.So is Christian faith and the ecclesial community of the faithful. We belong to one another, and our duty is to those who will come after us.

Saturday, October 21, 2006

Distant Mirrors

For obvious reasons, Virgil’s Aeneid is especially revered in Rome, for it is the story of the Trojan warrior who fled the burning citadel of Troy and, after many wanderings and arduous struggles, finally established the Italian foundations for what was to become the Roman civilization which Virgil had been commissioned to celebrate. There are many artistic depictions of one of the poem’s most riveting scenes: Aeneas, his small son Ascanius at his side, emerging from the flames of Troy carrying his father Anchises on his back, the old man clutching the household gods on whose protection he relies. In the pandemonium, Aeneas has been separated from his wife Creusa, who died in the Trojan conflagration.

Surely the most famous rendition of this poignant scene is the magnificent sculpture by Bernini, who captured the impact of the Trojan catastrophe at both the personal and cultural level. “Pious Aeneas” struggles to protect those he loves and to salvage what he can of a culture now overrun by its exultant conquerors, drunk with their victory.

As Liz and I stood before this exquisite masterpiece in the Borghese Gallery, it was difficult not to muse on its contemporary relevance. Ours is an age of refugees, many driven from their homes by violence and deprivation. But of course Aeneas was not a helpless peasant; he was a Trojan prince and warrior. Like so many people in history, he never imagined that his great culture could succumb to its enemies.

As Liz and I stood before this exquisite masterpiece in the Borghese Gallery, it was difficult not to muse on its contemporary relevance. Ours is an age of refugees, many driven from their homes by violence and deprivation. But of course Aeneas was not a helpless peasant; he was a Trojan prince and warrior. Like so many people in history, he never imagined that his great culture could succumb to its enemies.

Whenever one comes upon an artistic representation of Aeneas’ flight from Troy in a European gallery, one is very likely only a few steps away from another familiar artistic subject: a painting, sculpture, or bas relief of some famous battle at which Christian Europe has repelled an invading Islamic army or navy, narrowly avoiding Aeneas’ fate. The sheer number of such paintings is especially striking to an American tourist. The battles they depict began within just a few decades of the founding of Islam. Muhammad’s farewell address had commanded: “fight all men until they say, ‘There is no god but Allah,’” and his followers lost little time in carrying out his command.

After the early 8th century Moorish victories on the Iberian peninsula, resulting in a 700 year Islamic domination, Muslim armies crossed the Pyrenees only to be repelled at the Battle of Poitiers in 732 by Charles Martel, a victory which some historians regard as the single most important event in European history. (The single most important event in European history, of course, didn’t happen in Europe; it happened outside the walls of Jerusalem circa 30-40 A.D., but leaving that aside for the moment, the Battle of Poitiers looms large indeed in European history.) Had the battle gone the other way, Europe would almost certainly have become an Muslim society, and very likely remained so. Below is Charles de Steuben’s rendition of the battle that prevented this from happening.

– –

– –

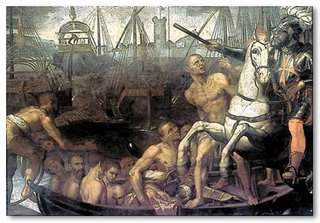

And then there is the Battle of Ostia, a naval battle fought in 849, depicted on a fresco by Raphael in the Vatican’s Stanza dell'incendio del Borgo.

– –

– –

And then there is the Siege of Vienna in 1529, here in a painting by Pieter Snayers the 17th century Flemish painter.

– –

– –

And then, of course, there is the famous naval Battle of Lepanto, in 1571, celebrated as the miraculous deliverance of Europe from what many feared would be the decisive Islamic invasion, rendered here by an unknown artist.

– –

– –

The victory at Lepanto was accompanied by the liberation of the Christian slaves who were chained to their oars in the galleys of the Turkish fleet.

G. K. Chesterton alluded to this liberation of Christian slaves in his famous poem Lepanto. Here are a few relevant lines:

G. K. Chesterton alluded to this liberation of Christian slaves in his famous poem Lepanto. Here are a few relevant lines:

But, alas, the word “finally” may no longer be apt. On the 318th anniversary of the day the Battle of Vienna began the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center were destroyed in what may well appear in historical hindsight as the beginning of a new Islamic offensive, one that the West cannot fathom because it is not animated by the materialist motives secular Westerners have come to believe drive history.

But, alas, the word “finally” may no longer be apt. On the 318th anniversary of the day the Battle of Vienna began the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center were destroyed in what may well appear in historical hindsight as the beginning of a new Islamic offensive, one that the West cannot fathom because it is not animated by the materialist motives secular Westerners have come to believe drive history.

This, oddly, brings us back to the Bernini marble and the destruction of Troy. For, in Shakespeare’s rendition at least, the fall of Troy was due as much to the reckless self-indulgence of the Trojan princes and the feckless folly of the Trojan elders as to the ferocity and cunning of the conquering Greeks. The Trojan catastrophe that ended with the Greek warriors spilling out of the Trojan horse to destroy Troy from within began with lust born of a vulgar mimetic triangle: Paris, Menelaus, and Helen.

As he did in so many of his later plays, Shakespeare, in his The Rape of Lucrece, saw the looming Trojan conflagration in the little spark of mimetically enkindled lust that ignited it:

We live in the waning days of the revolutions of 1968, when a disenchanted Marxism and an exhausted Freudianism fell into a carnal embrace, giving birth to a libertine Left as philosophically vacuous as it was politically reckless, unified only by its aversion to social conventions and the Judeo-Christian tradition that helped form them. Doting Priam did virtually nothing, as the children of this coupling, myself among them, stumbled into an anthropological experiment, the failures of which were thought to be due to the insufficient application of the ideological zeal that caused them. Slowly but surely, as the class of 1968 (so to speak) took control of one after another of the most important cultural institutions – the university, the churches, the media – the moral imagination of whole generations of the young began to be shaped by a naïve nihilism, most of whose proponents were too naïve even to realize how nihilistic their project was. (A glance at primetime television is proof enough.)

By the time its ideological pedigree had lost all its luster, the project had morphed into a moral relativism expressed in the comforting vocabulary of inclusion and multicultural sensitivity. In Europe especially, but on this side of the Atlantic as well, single-minded radical Islam has been able to cut through this moral muddle like a hot knife through butter – playing along with it when it’s convenient and mocking it when it isn’t. As Bruce Thorton put it, Europeans “through a neurotic nexus of spiritual exhaustion, colonial guilt, and multicultural sentimentalism, allowed Muslim immigrants to preach a virulent hatred of the West in schools and mosques frequently subsidized by state welfare payments.” This is today’s Trojan Horse, just as the feral, libertine politics of the secular Left is the analogue for the dalliances of Paris and Helen and the doting of old king Priam.

European society, having chosen a few decades ago to forgo the inconveniences and expense of childbearing and the family-fostering social commitments once considered culturally indispensable in favor of a reckless experiment in sexual normlessness, suddenly awoke to the fact that it takes 25 years to produce a generation of 25-year-olds, without whose participation in the labor force and tax base the social welfare programs to which most Europeans feel entitled would vanish. Under the circumstances, the aging European population turned to immigrants from largely Muslim societies. Both because beggars can’t be choosers and because it flattered the European self-estimation as broadminded multiculturalists, the newcomers were in no way encouraged to adopt and adapt to their host culture. On the contrary, a strong current of multicultural sentiment among the European elite regards the history of the West as something for which nothing but apologies are in order. Not surprisingly, sharing this Western self-loathing with the new arrivals from Muslim lands only reinforced what they had been taught in their Wahhabi schools, further convincing them of the validity of the other elements of the Wahhabi worldview.

How fitting an epitaph might those two lines of Shakespeare’s poem one day be for the cultural dissolution over which Europe’s 1968 generation (my generation) has presided:

Meanwhile, perhaps the single greatest cause for hope in Europe today is something that occurred on April 19, 2005 when Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, newly elected pope, chose St. Benedict as his pontifical patron. Benedict is the patron saint of Europe, the founder of the monastic order that preserved faith and learning through what is often called the Dark Ages. In choosing the name Benedict, the new pope signaled the priority the Church under his leadership would give to the European crisis. Determined not to forsake the continent in its hour of need, it is clear that Benedict will lead an effort to reawaken the Christian faith that made Europe what it once was and thereby to slowly revive its cultural self-confidence and historical hope.

Pope Benedict’s Regensburg University lecture, which has become so pivotal, was delivered on September 12th, the 318th anniversary of the day the day the Turks were turned back from the gates of Vienna. With consummate timing, impeccable scholarly finesse, and more charity than those who failed to read his lecture imagined, the pope that day broke the silence with a word of truth and candor, sending a message to both his interreligious dialogue partners and his fellow heirs of Western culture that the future of Europe and the West depends first and foremost on its commitment to truth and the courage of those willing to speak it.

My father, who was killed fighting the last great outbreak of anti-semitic barbarism, was born on this day in 1913. May he rest in peace.

Surely the most famous rendition of this poignant scene is the magnificent sculpture by Bernini, who captured the impact of the Trojan catastrophe at both the personal and cultural level. “Pious Aeneas” struggles to protect those he loves and to salvage what he can of a culture now overrun by its exultant conquerors, drunk with their victory.

As Liz and I stood before this exquisite masterpiece in the Borghese Gallery, it was difficult not to muse on its contemporary relevance. Ours is an age of refugees, many driven from their homes by violence and deprivation. But of course Aeneas was not a helpless peasant; he was a Trojan prince and warrior. Like so many people in history, he never imagined that his great culture could succumb to its enemies.

As Liz and I stood before this exquisite masterpiece in the Borghese Gallery, it was difficult not to muse on its contemporary relevance. Ours is an age of refugees, many driven from their homes by violence and deprivation. But of course Aeneas was not a helpless peasant; he was a Trojan prince and warrior. Like so many people in history, he never imagined that his great culture could succumb to its enemies.Whenever one comes upon an artistic representation of Aeneas’ flight from Troy in a European gallery, one is very likely only a few steps away from another familiar artistic subject: a painting, sculpture, or bas relief of some famous battle at which Christian Europe has repelled an invading Islamic army or navy, narrowly avoiding Aeneas’ fate. The sheer number of such paintings is especially striking to an American tourist. The battles they depict began within just a few decades of the founding of Islam. Muhammad’s farewell address had commanded: “fight all men until they say, ‘There is no god but Allah,’” and his followers lost little time in carrying out his command.

After the early 8th century Moorish victories on the Iberian peninsula, resulting in a 700 year Islamic domination, Muslim armies crossed the Pyrenees only to be repelled at the Battle of Poitiers in 732 by Charles Martel, a victory which some historians regard as the single most important event in European history. (The single most important event in European history, of course, didn’t happen in Europe; it happened outside the walls of Jerusalem circa 30-40 A.D., but leaving that aside for the moment, the Battle of Poitiers looms large indeed in European history.) Had the battle gone the other way, Europe would almost certainly have become an Muslim society, and very likely remained so. Below is Charles de Steuben’s rendition of the battle that prevented this from happening.

– –

– –And then there is the Battle of Ostia, a naval battle fought in 849, depicted on a fresco by Raphael in the Vatican’s Stanza dell'incendio del Borgo.

– –

– –And then there is the Siege of Vienna in 1529, here in a painting by Pieter Snayers the 17th century Flemish painter.

– –

– –And then, of course, there is the famous naval Battle of Lepanto, in 1571, celebrated as the miraculous deliverance of Europe from what many feared would be the decisive Islamic invasion, rendered here by an unknown artist.

– –

– –The victory at Lepanto was accompanied by the liberation of the Christian slaves who were chained to their oars in the galleys of the Turkish fleet.

G. K. Chesterton alluded to this liberation of Christian slaves in his famous poem Lepanto. Here are a few relevant lines:

G. K. Chesterton alluded to this liberation of Christian slaves in his famous poem Lepanto. Here are a few relevant lines:And above the ships are palaces of brown, black-bearded chiefs,Ten years ago, one would have concluded this chronicle of Islamic incursions into Christian Europe by drawing a line under it and saying something like: “And finally there was the decisive Battle of Vienna, September 11, 1683 (below), at which the Polish cavalry under Jan Sobieski defeated the Turks at the gates of Vienna.” The collapse of the Ottoman Empire after the First World War would have been further evidence that this centuries-old threat to Europe and the “West” had been superseded by perils more recognizable to those trained in the presuppositions of the European Enlightenment.

And below the ships are prisons, where with multitudinous griefs,

Christian captives sick and sunless, all a labouring race repines

Like a race in sunken cities, like a nation in the mines.

But, alas, the word “finally” may no longer be apt. On the 318th anniversary of the day the Battle of Vienna began the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center were destroyed in what may well appear in historical hindsight as the beginning of a new Islamic offensive, one that the West cannot fathom because it is not animated by the materialist motives secular Westerners have come to believe drive history.

But, alas, the word “finally” may no longer be apt. On the 318th anniversary of the day the Battle of Vienna began the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center were destroyed in what may well appear in historical hindsight as the beginning of a new Islamic offensive, one that the West cannot fathom because it is not animated by the materialist motives secular Westerners have come to believe drive history.This, oddly, brings us back to the Bernini marble and the destruction of Troy. For, in Shakespeare’s rendition at least, the fall of Troy was due as much to the reckless self-indulgence of the Trojan princes and the feckless folly of the Trojan elders as to the ferocity and cunning of the conquering Greeks. The Trojan catastrophe that ended with the Greek warriors spilling out of the Trojan horse to destroy Troy from within began with lust born of a vulgar mimetic triangle: Paris, Menelaus, and Helen.

As he did in so many of his later plays, Shakespeare, in his The Rape of Lucrece, saw the looming Trojan conflagration in the little spark of mimetically enkindled lust that ignited it:

Thy heat of lust, fond Paris, did incurMight the link between the mimetic crisis exemplified by Paris’ lust and the Trojans shock at finding their bitterest enemies armed and raging in their midst have a contemporary analogue?

This load of wrath that burning Troy doth bear:

Thy eye kindled the fire that burneth here;

And here in Troy, for trespass of thine eye,

The sire, the son, the dame, and daughter die . . .

. . . one man’s lust these many lives confounds:

Had doting Priam check’d his son’s desire,

Troy had been bright with fame and not with fire.

We live in the waning days of the revolutions of 1968, when a disenchanted Marxism and an exhausted Freudianism fell into a carnal embrace, giving birth to a libertine Left as philosophically vacuous as it was politically reckless, unified only by its aversion to social conventions and the Judeo-Christian tradition that helped form them. Doting Priam did virtually nothing, as the children of this coupling, myself among them, stumbled into an anthropological experiment, the failures of which were thought to be due to the insufficient application of the ideological zeal that caused them. Slowly but surely, as the class of 1968 (so to speak) took control of one after another of the most important cultural institutions – the university, the churches, the media – the moral imagination of whole generations of the young began to be shaped by a naïve nihilism, most of whose proponents were too naïve even to realize how nihilistic their project was. (A glance at primetime television is proof enough.)

By the time its ideological pedigree had lost all its luster, the project had morphed into a moral relativism expressed in the comforting vocabulary of inclusion and multicultural sensitivity. In Europe especially, but on this side of the Atlantic as well, single-minded radical Islam has been able to cut through this moral muddle like a hot knife through butter – playing along with it when it’s convenient and mocking it when it isn’t. As Bruce Thorton put it, Europeans “through a neurotic nexus of spiritual exhaustion, colonial guilt, and multicultural sentimentalism, allowed Muslim immigrants to preach a virulent hatred of the West in schools and mosques frequently subsidized by state welfare payments.” This is today’s Trojan Horse, just as the feral, libertine politics of the secular Left is the analogue for the dalliances of Paris and Helen and the doting of old king Priam.

European society, having chosen a few decades ago to forgo the inconveniences and expense of childbearing and the family-fostering social commitments once considered culturally indispensable in favor of a reckless experiment in sexual normlessness, suddenly awoke to the fact that it takes 25 years to produce a generation of 25-year-olds, without whose participation in the labor force and tax base the social welfare programs to which most Europeans feel entitled would vanish. Under the circumstances, the aging European population turned to immigrants from largely Muslim societies. Both because beggars can’t be choosers and because it flattered the European self-estimation as broadminded multiculturalists, the newcomers were in no way encouraged to adopt and adapt to their host culture. On the contrary, a strong current of multicultural sentiment among the European elite regards the history of the West as something for which nothing but apologies are in order. Not surprisingly, sharing this Western self-loathing with the new arrivals from Muslim lands only reinforced what they had been taught in their Wahhabi schools, further convincing them of the validity of the other elements of the Wahhabi worldview.

How fitting an epitaph might those two lines of Shakespeare’s poem one day be for the cultural dissolution over which Europe’s 1968 generation (my generation) has presided:

Had doting Priam check’d his son’s desire,Theodore Dalrymple is a physician who worked for many years in British prisons and among the most unfortunate in British society. He now lives in France. Here’s how he described the European situation in a recent article in the Claremont Review:

Troy had been bright with fame and not with fire.

They have either forgotten what it is to believe in anything, to such an extent that they cannot really believe that anyone else believes in anything, either; or their memories of belief are of belief in something so horrible -- Communism, for example, or Nazism -- that they no longer believe that they have the right to pass judgment on anything. This is not a strong position from which to fight people who, by their own admission, hate you and are bent upon your destruction ...Many of today’s clear-headed observers have begun to break the silence and suggest that Europe -- led by the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, England and France -- is drifting toward the stark choice between slow Islamization and civil war, or perhaps some very unpleasant combination of the two. One would very much like to believe that this is not the case, but events in Europe are far from reassuring, most distressing among them: the revival of forms of anti-Semitism to which both ends of the political spectrum have been willing to accommodate, and which is the mother's milk of jihadist Islam.

Meanwhile, perhaps the single greatest cause for hope in Europe today is something that occurred on April 19, 2005 when Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, newly elected pope, chose St. Benedict as his pontifical patron. Benedict is the patron saint of Europe, the founder of the monastic order that preserved faith and learning through what is often called the Dark Ages. In choosing the name Benedict, the new pope signaled the priority the Church under his leadership would give to the European crisis. Determined not to forsake the continent in its hour of need, it is clear that Benedict will lead an effort to reawaken the Christian faith that made Europe what it once was and thereby to slowly revive its cultural self-confidence and historical hope.

Pope Benedict’s Regensburg University lecture, which has become so pivotal, was delivered on September 12th, the 318th anniversary of the day the day the Turks were turned back from the gates of Vienna. With consummate timing, impeccable scholarly finesse, and more charity than those who failed to read his lecture imagined, the pope that day broke the silence with a word of truth and candor, sending a message to both his interreligious dialogue partners and his fellow heirs of Western culture that the future of Europe and the West depends first and foremost on its commitment to truth and the courage of those willing to speak it.

My father, who was killed fighting the last great outbreak of anti-semitic barbarism, was born on this day in 1913. May he rest in peace.

Friday, October 20, 2006

A Christian is someone who's met a Christian.

One of the most moving images I encountered in Rome, oddly enough, occurred in one of the many often kitschy religious article shops that surround the Vatican. It is a 1978 photograph of the greeting between the newly elected Pope John Paul II and then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict XVI.

What is called “apostolic succession” can become an dry formulaic argument. If its deep meaning and value are to be felt, we must not forget how simply human the concept is. Faith passes from one person to another, and the inspiration to proclaim it with conviction and charity is likewise received from those whose lives we admire and emulate, and who have, in one way or another, passed the mantel of mission on to us. This 1978 photograph represents for me one of the great mysteries of Christian faith, even as it gives a very human depiction of what apostolic succession really means.

According to my friend Giorgio Buccellati, Professor Emeritus of Ancient Near East and History at UCLA, Christianity depends on “an institutional charisma founded not on abstract legislation, but on personal bonding.” For, as professor Buccellati puts it, “… the ontic order is personal, and cannot be understood without reference to such a personal dimension …”

According to my friend Giorgio Buccellati, Professor Emeritus of Ancient Near East and History at UCLA, Christianity depends on “an institutional charisma founded not on abstract legislation, but on personal bonding.” For, as professor Buccellati puts it, “… the ontic order is personal, and cannot be understood without reference to such a personal dimension …”

Buccellati continues:

What is called “apostolic succession” can become an dry formulaic argument. If its deep meaning and value are to be felt, we must not forget how simply human the concept is. Faith passes from one person to another, and the inspiration to proclaim it with conviction and charity is likewise received from those whose lives we admire and emulate, and who have, in one way or another, passed the mantel of mission on to us. This 1978 photograph represents for me one of the great mysteries of Christian faith, even as it gives a very human depiction of what apostolic succession really means.

According to my friend Giorgio Buccellati, Professor Emeritus of Ancient Near East and History at UCLA, Christianity depends on “an institutional charisma founded not on abstract legislation, but on personal bonding.” For, as professor Buccellati puts it, “… the ontic order is personal, and cannot be understood without reference to such a personal dimension …”

According to my friend Giorgio Buccellati, Professor Emeritus of Ancient Near East and History at UCLA, Christianity depends on “an institutional charisma founded not on abstract legislation, but on personal bonding.” For, as professor Buccellati puts it, “… the ontic order is personal, and cannot be understood without reference to such a personal dimension …”Buccellati continues:

Sacramentality is rooted in face-to-face confrontation: it avoids the anonymity of a generic prayer felt only as wishful thinking. … [It] can be presented as a special dimension of human culture, namely, as … (1) the personal and physical contact embodied in the succession of an unbroken line of human individuals; (2) the physical property whereby the sacraments are given to us as the vehicle through which our individual sins are individually touched by redemption, with procedures that are normal for such transmission within human culture; and (3) the impact that sacramental presence has it touching all humans through other humans, again through a process analogously found in culture, where humans are purveyors of experience to each other. [Communio, Vol. XXX, No. 4, Winter 2003]

Thursday, October 19, 2006

"Let this mind be in you ..."

While hardly comparable to Bernini or Raphael or Caravaggio in other respects, the painting that stuck me with unusual power while we were in Rome was a painting of the Last Supper by the Italian painter, Jacopo Bassano. The painter has captured the blinding incomprehension of Jesus’ disciples as they lounge around, eating, squabbling, and chitchatting inanely. Christ is alone in their midst; he alone has a sense of what is happening and what is about to happen. Bassano has revealed, however, that in his solitude Christ remains in communion with his heaven Father.

While hardly comparable to Bernini or Raphael or Caravaggio in other respects, the painting that stuck me with unusual power while we were in Rome was a painting of the Last Supper by the Italian painter, Jacopo Bassano. The painter has captured the blinding incomprehension of Jesus’ disciples as they lounge around, eating, squabbling, and chitchatting inanely. Christ is alone in their midst; he alone has a sense of what is happening and what is about to happen. Bassano has revealed, however, that in his solitude Christ remains in communion with his heaven Father.Stepping into the Borghese Galley after a harrowing taxi ride through Roman traffic and recalling how the crowds of tourists roam seemingly aimlessly around the great churches of Rome, it was easy to recognize our world in this painting. Like Bassano’s disciples we often don’t have a clue as to the real drama of which we are unwittingly a part.

Here Christ seems not to be distressed by the incomprehension of his friends. Rather there is compassion in his face. He seems to know that he is about to enter into the greatest loneliness in the world. In exploring this the further reaches of loneliness, he opens up that terrain for all who will follow, and all will eventually follow. As Raymund Schwager of blessed memory puts it in his posthumously published Banished from Eden: Christ’s fate “makes clear that there is a final, unavoidable loneliness even for that creaturely freedom which the divine love completely permeates. But from this radical loneliness and freedom the new community arose.”

A few pages later, Raymund, who died unexpectedly not long after these words were written, says: “Supreme personal decision in one’s final, dying loneliness, and a total handing over to the other correspond to one another.”

Paul urges us: “Let this mind be in you which was in Christ Jesus.” A Christian should try to have Christ’s view of the world, not so as to affect a stoic detachment, but rather so as to love the distracted world the more.

Hans Urs von Balthasar describes the mind of Christ marvelously in this passage from Heart of the World (p.58ff):

Thus began his descent into the world. “Go there and set it in order,” the Father had said. And so he did come, and now he mingled as a stranger in the tumult of the market-place. He walked past the stands where the clever and the witty offered their wares for sale. He saw the vendors’ feverish hands as they rummaged through carpets and trinkets. He listened as skilled charlatans praised their own latest inventions: models for state and society, sure guides to the blessed life, machines to fly to the absolute, trapdoors and escapes into a blissful nothingness. He … peered through the curtain of inns where the absinthe of secret knowledge provides admission into artificial paradises and infernos. … A frightful noise, thick with the confusion of a thousand voices, went up from the throng. Dust and smoke whirled about, and everything gave off the sweetish smell of refuse and decay. No one knew the Father’s name.

Monday, October 16, 2006

This, in passing ...

This from Hans Urs von Balthasar:

“Noisy protests against war and famine in foreign lands and demagogic calls for the whole economic system to be changed are less effective than the quiet attention to what lies at hand, the conscientious development of real competence and the selfless investment of oneself -- and not at a tentative and dilettante level -- where the need is greatest. Through all this, there is a Providence that makes sure that the disproportion between the Goliath of the world powers and the Christian David remains a graphic one. It is not appropriate for David to strut around in the armor plating of power . . .”

Can this be true?

The Vatican Museum is of course too vast and too filled with great treasures to be absorbed in one visit. Liz and I had made two trips to the museum on our last trip to Rome a year and a half ago. This time we arrived at the museum too late in the day to do much more than see a fraction of its masterpieces. With the Cornerstone Forum’s “Emmaus Road Initiative” never far from my mind, I was taken by an especially fascinating tapestry among the truly stunning tapestry collections the Vatican houses. It is a tapestry from the Brussels workshop of the Flemish artist Pieter van Aelst dating from the middle of the 16th century. It depicts the moment when the two disciples with whom the risen Christ walked on the road to Emmaus recognize him in the breaking of the bread.

It is a very large tapestry, and the artist has depicted the two disciples in what appears to be a social hierarchy: the elder man on the left of the tapestry and a younger man slightly below him on the right. I was struck by something about which I will make more extensive comments in a subsequent post, namely, that Christ is looking at neither of the disciples, but rather he has his attention on something – or more precisely some One – else. Whereas Christ is exclusively constituted by, and consubstantial with, his heavenly Father, his Christian disciples depend on one another, that is to say, on the Church – the fellowship they have as a direct corollary of their newborn faith. What most fascinated me is the expression on the face of what appears to be the younger disciple on the right of the tapestry. He looks, not to Christ, but to his friend, his eyes asking in the most childlike way: “Can this be true?” If not, as Paul insists in the most unambiguous way, our faith is folly and lives lived according to it ridiculous.

It is a very large tapestry, and the artist has depicted the two disciples in what appears to be a social hierarchy: the elder man on the left of the tapestry and a younger man slightly below him on the right. I was struck by something about which I will make more extensive comments in a subsequent post, namely, that Christ is looking at neither of the disciples, but rather he has his attention on something – or more precisely some One – else. Whereas Christ is exclusively constituted by, and consubstantial with, his heavenly Father, his Christian disciples depend on one another, that is to say, on the Church – the fellowship they have as a direct corollary of their newborn faith. What most fascinated me is the expression on the face of what appears to be the younger disciple on the right of the tapestry. He looks, not to Christ, but to his friend, his eyes asking in the most childlike way: “Can this be true?” If not, as Paul insists in the most unambiguous way, our faith is folly and lives lived according to it ridiculous.

The Good Company Conference

I was in Rome to take part in a conference entitled "The Good Company: Catholic Social Thought and Corporate Social Responsibility in Dialogue." Since I was out of my depth at a conference on corporate social responsibility and only very slightly more up to speed on Catholic social thought -- the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church is a heavily annotated, 446 page treasure trove of insight) -- I had every reason to practice the virtue of modesty. Though some thought my paper a challenge to the conference presuppositions, I assured everyone that such was not my intention.

I was in Rome to take part in a conference entitled "The Good Company: Catholic Social Thought and Corporate Social Responsibility in Dialogue." Since I was out of my depth at a conference on corporate social responsibility and only very slightly more up to speed on Catholic social thought -- the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church is a heavily annotated, 446 page treasure trove of insight) -- I had every reason to practice the virtue of modesty. Though some thought my paper a challenge to the conference presuppositions, I assured everyone that such was not my intention. The conference was held as the venerable Pontifical University of St. Thomas (the Angelicum), home to a great deal of Catholic intellectual history.

The conference was held as the venerable Pontifical University of St. Thomas (the Angelicum), home to a great deal of Catholic intellectual history.My presentation, as I said in an earlier post, went well and was, as far as I could judge, quite well received. A lively and stimulating discussion followed.

Just as the last Roman conference at which I spoke occurred only three weeks after Liz's first brain surgery, this one occurred three weeks before her upcoming surgery. In both cases, we regarded the timing as providential, and we were able (thanks to the generosity of friends and the courtesy extended to us on both sides of the Atlantic) to turn a portion of our trip into a spiritual pilgrimage.

I will try to post again later today or tomorrow at the latest.

Saturday, October 14, 2006

Faith & Reason / History & Eschatology

The principle point of Benedict’s Regensburg University lecture, which caused such a storm a few weeks ago, was, to quote from the lecture, “the intrinsic necessity of a rapprochement between Biblical faith and Greek inquiry.” Presumptuous though it was for one as ill qualified as I am, I have argued in print and from many podiums that the intellectual enterprise to which the collaboration between theology and philosophy was devoted would be newly kindled and greatly advanced by an alliance between theology and anthropology, the latter built on the pioneering work of René Girard. It is nevertheless true that the quest for truth which the latter alliance would enhance would be in continuity with that which for centuries was nobly sustained those drawing on the Greek philosophical tradition and the Christian theological heritage. It was to this collaboration that Pope Benedict turned the attention of his Regensburg University audience:

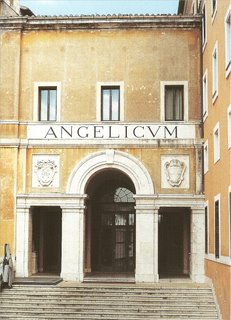

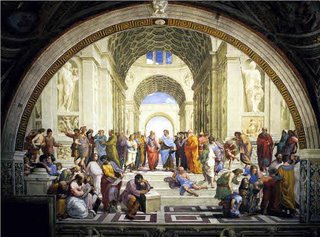

All of this came flooding in on me once again last week as Liz and I stood in the Stanza della Segnatura (a few steps from the Sistine Chapel) at the Vatican. For there the young Raphael, at the dawn of the modern age, gave perhaps the greatest artistic tribute we have to the deep interrelationship between faith and reason, one that amounts to a visual backdrop for the main point of Benedict’s Regensburg lecture. The room is dominated by the two giant frescos that face one another on opposite walls of the room and which serve in a way to interpret one another: The School of Athens and The Disputation on the Sacrament, commissioned by Pope Julius II and painted by Raphael in 1509 when he was only 27 years old.

Each of the frescos depicts the quest for truth in the form of lively philosophical-cum-theological discussions among those most committed to finding truth. The School of Athens depicts the great philosophers of the ancient world with Plato carrying his “Timaeus” and pointing heavenward and Aristotle carrying his “Nichmoachean Ethics” and pointing to the earth at the center of the fresco. The architecture of the School of Athens resembles the nave of the Basilica of St. Peter’s which Raphael’s friend Donato Bramante had begun in 1506, and which would have been recognized by Romans of the time. The architectural suggestion is clear, and it is precisely the suggestion Benedict make explicit in his lecture: that the efforts of Greek philosophy to extricate truth from myth serves in its own unique way as a praeparatio evangelica, a necessary preparation for humanity’s ongoing attempt to understand how its situation was fundamentally altered by the events of Golgotha and Easter. In the fresco other famous figures from the philosophical tradition are recognizable: Socrates, Heraclitus, Ptolemy, Euclid, and so on. Though some of the figures are alone and in thought, the overall feeling of the scene is of a philosophical movement toward the viewer, giving the sense that the philosophical past is moving toward the viewer and beyond toward the fresco on the opposite wall: The Disputation on the Sacrament.

In this fresco, the movement is away from the viewer with a decidedly vertical thrust to it. This shift from the horizontal to the vertical suggests something that is extremely important to our own predicament, namely, that an essential concomitant of the interplay of faith and reason is the interplay of history and eschatology. Raphael has depicted a “disputation” – that is a theological exploration – regarding the mystery of the Trinity and of Christ as represented by the Eucharistic sacrament, the viaticum Christ left as manna-like nourishment for the sustenance of his disciples in their arduous journey through history. The Disputation is divided horizontally between what the medievals called the Church militant (meaning those still struggling in the midst of a fallen world) and the Church triumphant (meaning those who had entered into the truth toward which the earthbound were still reaching).

There is ever so much more to find in these marvelous frescos, but simply standing between them was something of a religious experience, a reminder not only of the deep interrelationship between faith and rationality but, more importantly, of the liturgical meaning of history and the eschatological horizon which gives it its true meaning.

In point of fact, this rapprochement had been going on for some time. The mysterious name of God, revealed from the burning bush, a name which separates this God from all other divinities with their many names and simply asserts being, "I am", already presents a challenge to the notion of myth, to which Socrates' attempt to vanquish and transcend myth stands in close analogy. … This new understanding of God is accompanied by a kind of enlightenment, which finds stark expression in the mockery of gods who are merely the work of human hands (cf. Ps 115). Thus, despite the bitter conflict with those Hellenistic rulers who sought to accommodate it forcibly to the customs and idolatrous cult of the Greeks, biblical faith, in the Hellenistic period, encountered the best of Greek thought at a deep level, resulting in a mutual enrichment evident especially in the later wisdom literature. Today we know that the Greek translation of the Old Testament produced at Alexandria -- the Septuagint -- is more than a simple (and in that sense really less than satisfactory) translation of the Hebrew text: it is an independent textual witness and a distinct and important step in the history of revelation, one which brought about this encounter in a way that was decisive for the birth and spread of Christianity. A profound encounter of faith and reason is taking place here, an encounter between genuine enlightenment and religion. …If the task of extricating truth from myth is fundamental to biblical religion, the contribution that Girard has made constitutes, as I have said, an extraordinarily important turning point. This is especially so in light of the multicultural environment in which this task is today necessarily being undertaken, and that multicultural environment was clearly uppermost in Benedict’s mind, for on the recovery of a genuine and determined quest for truth the future of Europe and of western civilization depends.

This inner rapprochement between Biblical faith and Greek philosophical inquiry was an event of decisive importance not only from the standpoint of the history of religions, but also from that of world history - it is an event which concerns us even today. Given this convergence, it is not surprising that Christianity, despite its origins and some significant developments in the East, finally took on its historically decisive character in Europe. We can also express this the other way around: this convergence, with the subsequent addition of the Roman heritage, created Europe and remains the foundation of what can rightly be called Europe.“The fundamental decisions made about the relationship between faith and the use of human reason,” writes Benedict, “are part of the faith itself; they are developments consonant with the nature of faith itself.”

All of this came flooding in on me once again last week as Liz and I stood in the Stanza della Segnatura (a few steps from the Sistine Chapel) at the Vatican. For there the young Raphael, at the dawn of the modern age, gave perhaps the greatest artistic tribute we have to the deep interrelationship between faith and reason, one that amounts to a visual backdrop for the main point of Benedict’s Regensburg lecture. The room is dominated by the two giant frescos that face one another on opposite walls of the room and which serve in a way to interpret one another: The School of Athens and The Disputation on the Sacrament, commissioned by Pope Julius II and painted by Raphael in 1509 when he was only 27 years old.

Each of the frescos depicts the quest for truth in the form of lively philosophical-cum-theological discussions among those most committed to finding truth. The School of Athens depicts the great philosophers of the ancient world with Plato carrying his “Timaeus” and pointing heavenward and Aristotle carrying his “Nichmoachean Ethics” and pointing to the earth at the center of the fresco. The architecture of the School of Athens resembles the nave of the Basilica of St. Peter’s which Raphael’s friend Donato Bramante had begun in 1506, and which would have been recognized by Romans of the time. The architectural suggestion is clear, and it is precisely the suggestion Benedict make explicit in his lecture: that the efforts of Greek philosophy to extricate truth from myth serves in its own unique way as a praeparatio evangelica, a necessary preparation for humanity’s ongoing attempt to understand how its situation was fundamentally altered by the events of Golgotha and Easter. In the fresco other famous figures from the philosophical tradition are recognizable: Socrates, Heraclitus, Ptolemy, Euclid, and so on. Though some of the figures are alone and in thought, the overall feeling of the scene is of a philosophical movement toward the viewer, giving the sense that the philosophical past is moving toward the viewer and beyond toward the fresco on the opposite wall: The Disputation on the Sacrament.